GREAT question. Maybe someone else could explain it better than me, but here’s how I’d go about it:

I think there are two concepts that need to be explained. First, how Turing Tumble relates to what’s inside a computer chip. And then second, how you get from that to a more complicated system that can draw numbers on a screen.

1. How is Turing Tumble like an electronic computer?

Computers contain lots and lots of switches. How can switches do anything smart? Well not all switches can. For example, the switch on my wall can’t do anything smart at all - it just turns on and off the light. It can’t do anything more complicated because it’s a switch that turns electricity on and off, but it’s flipped mechanically. In order for switches to do anything more complicated, they have to be able to flip each other on and off. That means the switch needs to be flipped on and off using the same type of energy that it turns on and off. So an electrical switch would need to be flipped by electrical energy, and a mechanical switch would need to be switched by mechanical energy.

Regular electronic computers have tiny electrical switches that are flipped by electricity. They’re called “transistors”. They’re connected to each other with tiny copper wires inside computer chips. You can see kind of what they look like in this video. Notice how there are layers of wires. The layers make it possible for wires to cross over each other without touching.

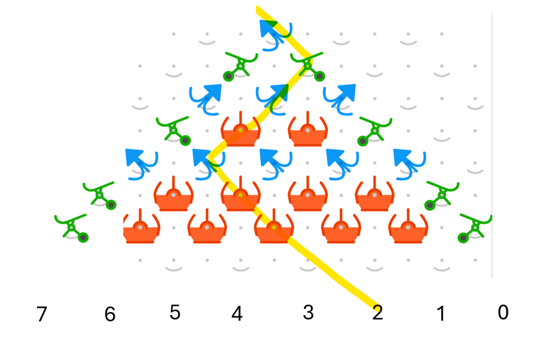

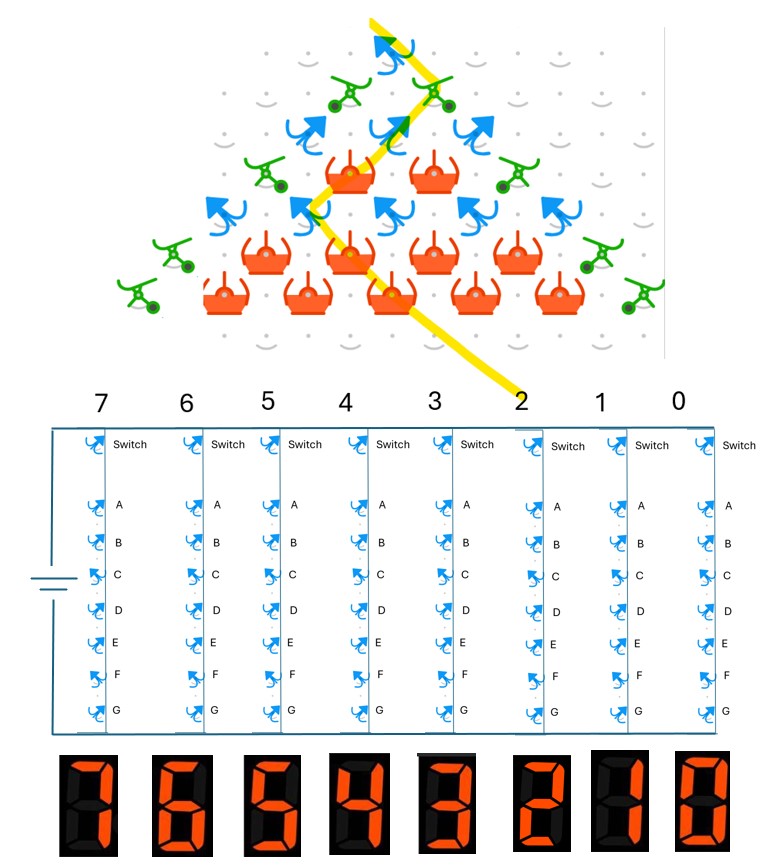

In Turing Tumble, the ramps are like wires. They make paths that the balls must follow. The crossovers are like wires that cross over one another without touching. The switches are the bits and gear bits. They control something mechanical (whether a ball exits to the left or the right) and they are also flipped mechanically (when a ball lands on them).

Turing Tumble lets you see how switches can do logic and smart things, just like in an electronic computer.

2. How do you get from the little circuits you build in Turing Tumble to a more complicated computer that can display numbers on a screen?

Turing Tumble gives you the basic tools to build a more complex system, but it would take a much bigger board to be able to do everything a full computer processor does. You could start to imagine how it would look, though.

First of all, it would have memory. The memory would be a bank of bits where information can be stored and retrieved. That memory would be split into two types: program memory, where instructions are stored, and data memory, where numbers and other random bits of information are stored.

The processor would also have a small number of registers - maybe 8. Whereas memory is for storing information, registers are like the workspace of a processor. The processor copies information into the registers from memory, does something to that information, and then copies it back into memory when it’s done. It copies the information back to memory because it can’t hold the information there forever since there are only 8 registers.

So when it’s running, the processor would copy instruction codes one by one out of program memory, into the processor’s workspace, and do what they say to do. For example, the following four instructions would add two numbers together and store the sum in data memory:

Instruction Code #1: 23, 256, 1

In this case, ‘23’ is a code that says to copy something out of memory. ‘256’ is the starting memory bit to copy data from, and ‘1’ says to copy it to register 1.

Instruction Code #2: 23, 264, 2

The second instruction code says to copy the data starting at position 264 in the memory bits into register 2.

Instruction Code #3: 12, 1, 2, 3

In this case, ‘12’ is the code to add two numbers together. The processor adds the numbers stored in registers 1 and 2 and stores the sum in register 3.

Instruction Code #4: 24, 3, 272

In this case, ‘24’ is the code to copy something back into memory. The instruction says to copy whatever is in register 3 into memory starting at memory bit 272.

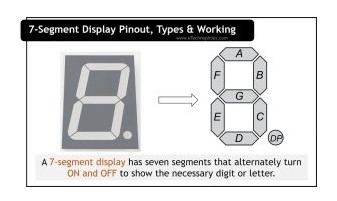

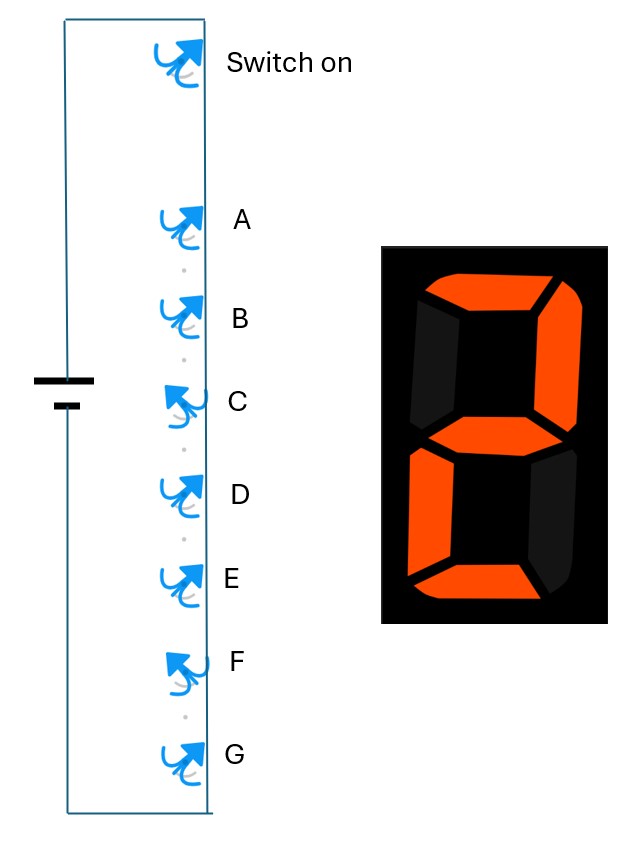

Hopefully that gives a feel for how the processor works. Now for displaying a number on a screen. A black and white monitor is also just a bank of switches - on or off, white or black. The switches are arranged in a grid on the screen, each switch controlling a pixel on the screen. When you want to turn a pixel on or off, you turn the switch on or off.

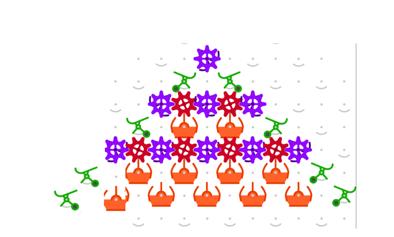

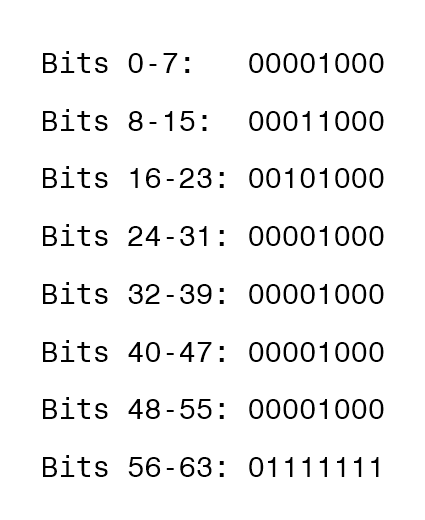

If you wanted to display a number on the screen, you’d have to first grab the number you want to display out of data memory. Somewhere in data memory, you’d also need to have pictures of each number stored, sort of like this:

That would be the number one.

To display the number ‘1’, your program would have to copy those bits to the bits on the screen. To show numbers other than ‘1’, your program (that is, the series of instructions in program memory), would need to check the number you want to display and copy over the right image. Is it a 1 (00000001)? Copy the ‘1’ image bits to the screen. Is it a 2 (00000010)? Copy the ‘2’ image bits to the screen. Is it a 3 (00000011)? Copy the ‘3’ image bits to the screen. And so on…

Does that help? If something isn’t clear or doesn’t make sense, say the word and I’ll try to improve this explanation.

Hopefully both perspectives are interesting and useful.)

Hopefully both perspectives are interesting and useful.)